When IBM chairman Thomas Watson was selected to serve as ambassador to the USSR in 1979, he had a problem. Ethics norms of the time dictated he needed to dispose of his personal stakes in several VC funds he’d accumulated over years of investing in the early computing industry. Watson tapped Dayton Carr to help market the fund interests. After significant effort, Carr was able to find willing buyers in the nascent private markets ecosystem to complete the sales. This convinced Carr to set up the world’s first dedicated secondaries firm, Venture Capital Fund of America, to pursue the strategy full-time.1 Carr ended up nurturing several industry luminaries, including Jeremy Coller (CEO of Coller Capital) and Andrew Isnard (CEO of Arcis Group).

Today, the industry Carr helped birth transacted $112B of volume in 2023 and has spread into every private asset class.2 Whether because of competitive returns, diversification, or quicker cash conversion cycles, secondaries have become an increasingly important arrow in the quiver of private market allocations available to investors. This article will walk through two common types of secondaries deals, recent trends in different corners of the market, and things for investors to keep in mind before jumping in.

Watson’s quandary is an example of the original form of secondaries transactions, LP stake sales. These involve Limited Partners (LPs) looking to sell private fund interests and secondaries managers hoping to acquire them for less than their intrinsic value. LPs might be looking to sell because of shifting strategic mandates, idiosyncratic personal factors, loss of conviction in a manager’s strategy, or to free up liquidity. Buyers are tempted by typical discounts to Net Asset Value (NAV) at purchase, a shorter runway to liquidity as typical sales take place in the latter years of a fund’s life, and a mostly known and well-diversified portfolio.

Many private fund contracts require General Partner (GP) consent before interests are transferred, which means the GP must approve LP stake purchasers before any sale. This is especially true for Venture managers, who can be sensitive about allowing new investors into the partnership who might publicize portfolio company information. These dynamics help existing LPs in a fund get a leg up when purchasing stakes, as they can be trusted not to circulate information and are knowledgeable enough about the portfolios to ascertain their true value. Because that pool of LPs is often smaller than buyout funds, bidding for venture portfolios tends to be less competitive.

As secondary markets developed, a pattern of LPs looking to unload interests in long-dated funds emerged. Because fund interests might be a bit small by that stage of a fund’s life, LPs might not get great asset pricing. GPs became aware of this dynamic and introduced continuation funds, where LPs would be given the option to sell their interests in one large block and hopefully fetch a better price. GPs are quite enthusiastic about the prospect as it allows them to reap significant carry when LPs extinguish their fund interests and restart the clock on fee income (which GPs receive from new purchasers in exchange for continued management of the assets). Less cynically, they can also allow GPs to pursue more long-term value enhancement plans rather than forcing assets to market prematurely.

From a purchaser’s perspective, continuation vehicles offer the chance to purchase significant exposure to a concentrated portfolio. Because managers typically run a bidding process for the right to participate, secondaries purchasers can get an opportunity to learn more about the assets they’re purchasing, particularly if they are less familiar with the manager. In the words of one market participant, “Managers can sell these assets to any number of people.”3 This same broadly marketed process usually means more competitive pricing, requiring purchasers to be spot on when forecasting portfolio company growth.

Whether on the LP or GP side, this market environment has been conducive to significant secondaries volume. Jefferies estimates that 2023 was secondaries’ second-largest year behind 2021, with volume fairly evenly split between GP continuation vehicles and LP stake sales.2 LP volume was dominated by Pensions and Sovereign Wealth Funds, which is perhaps unsurprising as they are the largest individual pools of capital. On the GP side, higher rates made the traditional exit routes of IPOs, M&A, and dividend recaps scarce, creating a strong opportunity for continuation funds to provide liquidity. Continuation funds reached an all-time high of 12% of global sponsor-backed exits, more than double the average for the previous 3 years.2

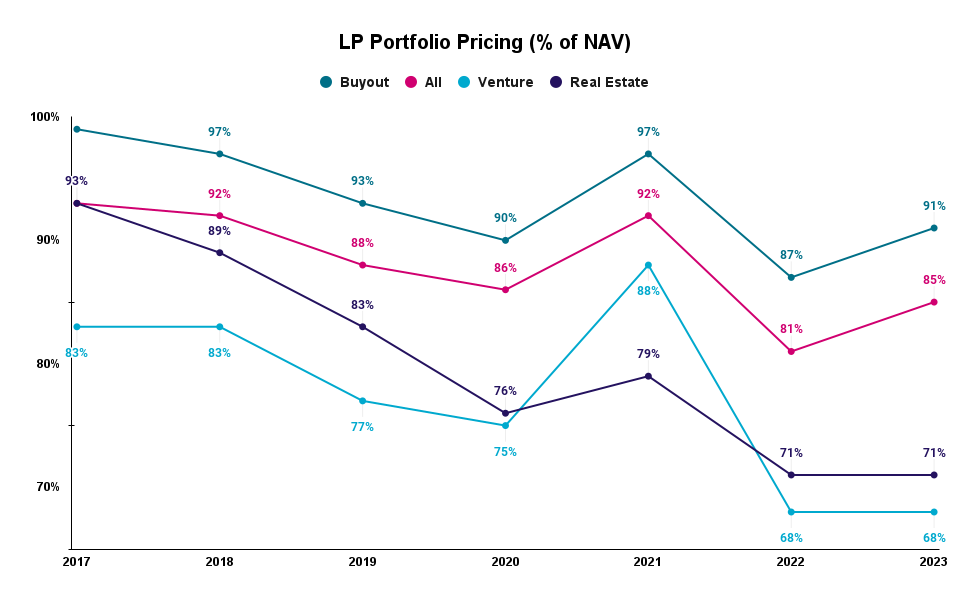

The thirst for liquidity has had a knock-on effect on pricing. Below, you’ll find a graph of annual pricing on LP deals across asset classes, where eagle-eyed readers will note that every asset class priced below its pre-COVID average in 2023. However, this was far from evenly distributed as buyout deals rebounded to 91% of NAV while venture pricing remained depressed at 68% of NAV. Part of this spread is due to differences in valuation policies, as buyout managers are often slower to write up portfolio companies than VCs, who typically write up portfolio companies every 1-3 years as they raise additional rounds of capital.4 Those external VC rounds are usually a strong anchoring point for venture valuations, which means that venture managers are slower to write down the value of their portfolios in a downturn.

Beyond technical pricing differences is a supply and demand mismatch. Jeffries pegs the dedicated capital available to pursue secondaries at an all-time high of $255B or 2.3x the market’s volume.2 Most of this dry powder has been raised to pursue buyout opportunities, including $23B for Lexington Partners’ latest fund5 and $25B for Blackstone’s most recent vintage.6 By contrast, the closed nature of many venture secondaries opportunities, smaller opportunity sets, and the higher bar on the diligence of rapidly changing venture-backed companies makes it more difficult to deploy capital at scale. This shows up in the fundraising figures, with the largest secondaries fundraises dedicated to venture Industry’s recent $1.7B vintage7 or StepStone’s $2.6B 2021 close.8

Finally, investors should consider how private secondaries compare with public markets. In the past year, the S&P 500 is up 28%, and the NASDAQ-100 is up 50%.9 Cambridge Associates’ most recent one-year buyout performance was pegged at 6.4%, while venture turned in a -10.4% return.10 So while private company valuations might have looked stretched relative to their public peers in 2023, the growth of public comps mainly fueled by multiple expansion makes the concern less salient in 2024.11

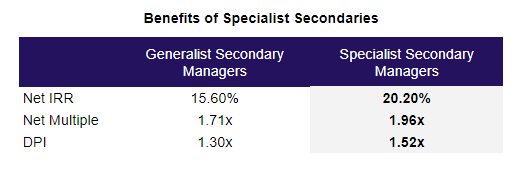

There is strong evidence that more niche secondaries managers engaging in less competitive bidding processes can produce outsized returns. Phil Huber at Cliffwater recently put out a note that segments the secondaries landscape into generalist firms with larger fund sizes and broader remits and specialist firms focusing on a narrower slice of the market.12 He found that Specialists outperformed by ~5% per year across a 250 fund dataset. This makes sense, as we would expect excess returns to be eroded in markets with more dry powder outstanding.

Bringing it all together, investors can benefit significantly from secondaries funds due to a faster payback period than primary investments, increased diversification, and competitive returns. Now is a particularly advantageous time to tap the secondaries markets with discounts to NAV above pre-COVID averages across asset classes and even further above average in more niche spaces like venture. Higher prices for public stocks make these entry points more valuable on a relative basis. When considering how to play the space, investors should consider the degree to which specialization gives a manager they are considering partnering with a relative advantage.

In 1969, a team of researchers at UCLA sent the first message between two computers to Stanford on the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET). Often known as the forerunner of the internet, ARPANET was funded by the Department of Defense to link research institutions with government grants to speed technological development. It only took a few years for one of the academics, Bob Thomas, to create a program named Creeper that could track network activity and report back its findings. This was quickly followed by Ray Tomlinson’s Reaper antivirus software, which chased and deleted Creeper wherever it was found.

This tit-for-tat between Bob and Ray is the first example of cybersecurity in action, and for the past five decades, the battle between those looking to penetrate online networks and those erecting defenses has continued to escalate. In 2023, end-user spending in the market for information security from cyber attacks was projected to reach $188B, which would represent 11.3% growth from 2022. Estimates for how large this market can get vary widely, but a study by McKinsey pegged the top end at $2 trillion.

Why does such explosive growth appear likely? One way to approach that question is to consider how much cybercrime costs today and how that’s likely to change. The team at Cybersecurity Ventures estimated that cybercrime would cost $8 trillion in 2023 and $10 trillion by 2025 due to a host of costs, including data destruction, stolen money, IP theft, and reputational harm, among others. Another barometer includes surveys of top executives purchasing cyber defenses as they are the ones writing the checks. Morgan Stanley asked 100 Chief Information Officers in early 2023 about which programs would receive the largest spending increase, and Security Software came first.1 More revealingly, when asked which programs are most likely to be cut, none of the CIOs mentioned Security Software.

Not only is explosive growth possible, but there are reasons to believe startups will have an outsized role to play in defending against the next generation of attackers. One is that entrepreneurs can structure their firms to prevent today’s threats. Cyber professionals have already started to see Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) contribute to cyber attacks by making it cheaper for groups to run spear phishing or automated customer support scams. The US government has noticed, setting up an AI Security Center within the National Security Agency (NSA) to guard sensitive information that can’t always be addressed with third-party software. Similarly, advances in quantum computing threaten to make many current encryption methods obsolete. Companies built to stop these new vectors of attack stand to benefit if they can outperform legacy players, and historically, incumbents have struggled to innovate on new products while staying at the cutting edge of their existing products. This is especially easy because experienced cyber operators can offer consulting services independently to generate revenue while developing the next software program to productize their insights.

Considering the size and growth of the cyber market, you might expect the venture industry to be rushing headlong into cyber. TechCrunch’s data disagrees, and they estimate Security startups only raised $2.7B in funding over the first quarter of 2023, down 58% year over year. Beyond a general funding malaise, VCs also might be reacting to the difficulties in investing in the space as a generalist. Cyber-specific VCs enjoy advantages on the sourcing side because their relationships with executives purchasing cyber solutions can help startups get a foot in the door with potentially huge clients. They are also advantaged with investment diligence because extensive experience allows them to more easily separate overhyped players from true security breakthroughs. This is crucially important in an industry where companies can grow revenue before the flaws in their security solutions manifest.

Cybersecurity is an industry ripe for continued growth and disruptive innovation. As investors consider how they want to position portfolios against potential disruptions from AI or quantum computing, it would be wise to consider how cybersecurity investments could function as an (imperfect) hedge. We are excited to see how the space develops in the years ahead and hope that those building protective walls outpace bad actors seeking to scale them.

In a world where industry giants often dominate the headlines, there’s an under-the-radar category of companies poised for explosive growth: micro-multinationals.

With turnovers ranging from $50 million to $250 million, these agile and innovative entities are bridging the gap between startups and established multinational corporations. Micro-multinationals present an unprecedented opportunity for the discerning investor to achieve stellar returns while diversifying internationally.

Micro-multinationals are mid-sized companies expanding beyond their home markets and establishing an international presence. According to an HSBC report, UK-based SMBs generate roughly 66% of their revenues outside their home market. That figure is expected to grow as 83% of SMBs cite overseas expansion as their top priority.

These companies are not just trading with international counterparts but are actively setting up operations in new markets, evolving from import/export entities into truly multinational businesses.

One of the defining characteristics of micro-multinationals is their agility. They are often faster to innovate and more adept at adopting new technologies than more giant corporations. This agility enables them to respond to market changes and capitalize on emerging trends quickly.

Plus, micro-multinationals tend to focus their value propositions around products or competencies where they have specialized expertise, allowing them to capture niche markets with precision.

Micro-multinationals offer a compelling opportunity for investors seeking higher returns and international diversification. Investing through private markets enables investors to access these high-potential entities with lower capital requirements than traditional investments in large multinational corporations.

Early-stage venture funds return average net annual returns of over 21%, compared to just 12.6% for late and expansion-stage funds. When companies are rapidly growing, their valuations can increase significantly in a relatively short period. Their innovative products or services often cater to a global market, and as they expand internationally, they can achieve economies of scale and access larger customer bases.

Also, micro-multinationals are often pioneers in their industries. Investing in these companies can reap the benefits of first-mover advantage. These companies may introduce new technologies or enter markets that have not yet been saturated, giving them an edge over competitors.

Of course, investing in early-stage micro-multinationals is inherently riskier than investing in established companies. These companies may not have a proven track record, and their success often hinges on the ability to execute their business model effectively. And, since they operate internationally, they are exposed to additional risks such as currency fluctuations, geopolitical tensions, and regulatory changes.

Given the high-risk nature of investing in early-stage micro-multinationals, investors must have a well-diversified portfolio. This can be achieved by spreading investments across different industries, geographic regions, and stages of company development.

Platforms like Gridline are making it easier than ever for investors to tap into the world of micro-multinationals. Gridline offers access to top-tier diversified opportunities vetted and curated by experts, providing investors with the tools they need to capitalize on this emerging international business category.

2023 is turning out to be a gold rush year for Artificial Intelligence investments. Up to half of this year’s stock market gains are due to the buzz around disruptive technologies in AI, and AI unicorns are being churned out at a blistering pace.

This boom is rooted in some of the greatest technological advancements in decades (potentially depending on how room-temperature superconductors pan out). Notably, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has achieved a level of sophistication in generating text, code, images, and audio that is close to par with human abilities.

To make informed investment decisions around AI, it’s important to understand the landscape, including the technologies, the applications, and the industries AI is disrupting.

Venture investment in AI is exploding largely thanks to one technology called Transformers. First introduced in a 2017 research paper, Transformers have enabled the development of highly sophisticated natural language processing, like large language model technology tech-giant OpenAI, segwaying into GPT and BERT.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT has been the market leader for machine learning and natural language processing, becoming the fastest-growing application in history, reaching 100 million users just two months after launching. But, new tech companies like AI21 Labs, Anthropic, and Cohere are nipping at its heels with vast growth potential in natural language processing. For investors, backing companies that are displaying growth potential in AI algorithms can be a play toward owning a piece of the brainpower that drives many applications.

Shifting the focus to vision, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) are used for generating images, audio, and videos. Companies like RunwayML are advancing in this space, and investment in vision models can be seen as a bet on industries like healthcare, automotive, and retail, where visual data is paramount.

In the booming AI industry, tech companies selling AI hardware can be compared to “selling shovels in a gold rush.” Nvidia is the behemoth in this space, but there’s a burgeoning scene of startups striving to build the next generation of AI chips.

Take Sapeon, for instance. This South Korean startup is making waves in the AI chip market by designing specialized AI semiconductors for data centers. With a recent funding round, Sapeon’s valuation has soared above $400 million, marking its growing presence in the AI hardware space.

Another big contender is GrAI Matter Labs, which claims to offer better performance than Nvidia. By focusing on optimizing performance, GrAI Matter Labs is positioning itself as an alternative for those seeking more processing power in their AI applications.

But algorithms and hardware are just part of the story. Data is the fuel that powers AI, and high-quality data is indispensable for training robust AI models, fine-tuning their performance, and ensuring their real-world applicability.

One startup that’s making strides in this domain is Scale AI. As of April 2021, the company has raised a total of $603 million over six funding rounds and was last valued at over $7 billion. Its growth underscores the burgeoning demand for high-quality data in AI applications.

Scale AI operates in a competitive market with players like SuperAnnotate, Dataloop, Fastagger, and V7, among others. As AI applications continue to proliferate, the demand for data is bound to surge, making data-providing companies an invaluable piece of the AI investment puzzle.

Once you have the algorithms, hardware, and data, the next step is applications. Copywriting and marketing, in particular, have greatly benefited from AI. Copy.ai and Jasper.ai, for instance, have raised over $100 million to automatically generate compelling marketing copy and content for thousands of businesses.

Another area where AI is revolutionizing consumer applications is photo and video editing. Facetune, which recently raised $10 million, and Stability AI, which raised $100 million, are two examples. These applications let users generate AI selfies and more for pennies that artists used to charge hundreds of dollars for.

While consumer applications offer impressive prospects, it’s important for retail investors not to have tunnel vision when making investment decisions. AI is also making groundbreaking advancements in industries such as healthcare, finance, and manufacturing- providing AI exposure to a diversified portfolio of companies for savvy investors. For example, AI-powered diagnostic tools are improving patient care, while AI algorithms are being used to predict stock market trends with surprising accuracy.

Given that AI innovation is happening in these relatively small upstarts, gaining access to private market investment opportunities is essential. Gridline offers a gateway for accredited investors to access private markets, enabling them to participate in early-stage investments that have the potential to yield significant returns.

Relatively few businesses ever get VC funding, but this small group often evolves into industry giants. Just five VC-funded companies—Microsoft, Google, Nvidia, Apple, and Meta—account for the entire year-to-date return of the stock market. Yet, the returns achieved in the public market pale compared to the gains realized by early-stage investors.

This illustrates how private market investors, through their early stake in these tech titans, reap substantial benefits before companies go public. The next wave of innovation—and returns—will emerge from venture investments in AI yet to debut on the public market.

AI is seeing an annual growth rate of 37%, and the market is expected to reach $407 billion by 2027. It’s no wonder, then, that investors are clamoring to take advantage.

Up to 50% of this year’s stock market gains owe to “the buzz around AI.” On the private market front, 8 new AI unicorns, or billion-dollar startups, were created by May of this year. There’s also been a 49.7% quarter-over-quarter growth in private market investment in AI.

The most-hyped (and most-funded) among these is OpenAI, a private company that landed a $10 billion round from Microsoft in January. OpenAI’s journey as an AI research lab to one of the most valued AI companies globally is a prime example of the potential private market investments hold.

Launched in 2015, its mission was ambitious: to ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI)—highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work—benefit all of humanity. The organization committed to focusing on long-term safety and technical leadership and vowed to stop competing and start assisting any value-aligned, safety-conscious project that comes close to building AGI before them.

However, in 2019, OpenAI restructured itself into a “capped-profit” model, acknowledging that it required unprecedented amounts of resources to fulfill its mission and compete with other well-funded AI research entities. This strategic shift was a pivotal moment that set the stage for significant private investment opportunities.

Microsoft’s substantial investment underscores a critical truth in today’s investment landscape: real wealth is being created in the private markets well before companies reach the public sphere.

Historically, companies would turn to the public markets for growth capital. But today, due to the ample liquidity in private markets, companies can stay private longer, scaling their operations without the added pressures of quarterly earnings and public scrutiny.

When it comes to capturing the explosive growth of AI, traditional indices like the S&P500 are not the best investment vehicles. By the time established companies like Google make significant strides in AI, their stock prices might not reflect the kind of exponential growth that early-stage private AI companies experience.

For instance, Google tried to capitalize on the AI hype with its project, Google Bard. This project aimed at revolutionizing search through AI. However, it turned out to be a failure due to various technical mishaps, causing their market cap to drop by $100 billion. Despite Google’s 40% price surge this year, it’s still down around 17% from its peak.

Another example is IBM, which despite its early involvement in AI with the famous Watson, has struggled to monetize and keep pace with newer AI startups. In fact, IBM’s stock price hit $131 during the dot-com boom prior to Watson’s release. As of writing, it sits at $130. Clearly, being an early player in AI does not translate into stock market gains, especially for large, established companies.

This is where the private market comes into play. Companies like OpenAI, which are not yet publicly traded, represent the forefront of AI innovation and are growing exponentially. In 2020, OpenAI was valued at around $15 billion. Today, it’s worth $29 billion.

Investors looking to capitalize on AI innovation must look towards the private markets. Through venture capital and private equity investments in AI, investors can gain exposure to the high-growth potential before these companies go public and reach more mature stages of their lifecycle.

In the public equity markets, top-performing and bottom-performing managers provide returns within a relatively tight band. For example, the 5th percentile of managers returns around 5%, and the 95th percentile is around 10%. Further, persistence is almost non-existent: the top-performing managers in one year are unlikely to repeat their performance in subsequent years, and neither are the bottom performers.

In contrast, the dispersion of returns is much wider in the venture capital (VC) industry. The 5th percentile of managers lose money, and the 95th percentile returns over 40%. Further, persistence is strong: the top-performing VCs in one year are likelier to repeat their performance in subsequent years than the bottom performers.

One study finds a correlation of nearly 0.7 between a VC’s return in one year and its return in the next year. This research isn’t alone; Morgan Stanley points to “other researchers, using different data and methods, [who] find continued evidence of persistence.”

This means that the best VCs are much more likely than the average public equity manager to generate significant outperformance. Fund selection is critical in VC and worth paying attention to a VCs track record. That said, there are many other factors at play in VC—the stage of the company, the industry, the quality of the management team, and so on—so fund selection is only a part of what goes into a successful investment.

There are a few possible explanations. For one, VCs invest in entrepreneurs, and entrepreneurs with a track record of success are more likely to be successful again. In fact, Harvard research shows that a successful VC-backed entrepreneur has a 30% chance of succeeding in his next venture, while first-time entrepreneurs have only a 21% chance. Accessing these serial entrepreneurs is a key to successful VC investing, and the best VCs have a network of them.

Another explanation is that early VC success “leads to investing in later rounds and larger syndicates,” which means that top-quartile VCs have greater access to deal flow. This preferential access gives them an informational edge, leading to better returns. Access-constrained funds, or those with greater access to privileged opportunities, outperform across the board.

Further, a recent Oxford Journal paper theorizes that “successful funds receive continuation contracts that tolerate investment failure and encourage innovation.” In other words, the best VCs are given more leeway to take risks, which leads to more success.

The simplest explanation is that top-quartile VCs are better at what they do. They have a superior understanding of the startups in their portfolio and are better at working with entrepreneurs to help them grow their businesses. These advantages compound over time, leading to better and better performance.

This isn’t to say that all VCs are created equal; the best have a rare combination of skills, experience, and networks. But if you’re looking to invest in VC, it’s important to consider persistence. The best funds have a strong track record of delivering superior returns and are more likely to do so in the future.

Gridline considers all these factors when curating a selection of professionally managed alternative investment funds for individual investors. With lower capital minimums, fees, and greater liquidity, Gridline is the most efficient way to gain diversified exposure to non-public assets.

A key part of the startup ecosystem went up in flames with the sudden collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). When the Federal Reserve began hiking interest rates, it started a chain reaction that led to the bank’s demise, largely due to its complete failure to hedge interest rate risk.

The higher interest rates put pressure on tech stocks, eroded the value of SVB’s bonds portfolio, and caused venture capital to pull back. After SVB announced that it would sell $2.25 billion in new shares, panic and fear spread among venture capitalists, and SVB stock started to decline rapidly. Within 48 hours, a run on SVB to the tune of $42 billion had taken place, forcing regulators to intervene and shut down the bank. Soon after, the FDIC moved to guarantee deposits beyond the standard limit.

Despite this guarantee, the investment community is worried about the current state of VC. With one of the major banks in the industry gone, there is a fear that venture capitalists will become more cautious with their investments.

SVB has done business with nearly half of all US tech startups backed by venture capital, and, likely, VCs will now be more risk-averse. This could mean companies will have a harder time getting funding as VCs become more selective. Further, VCs may also demand more in terms of equity for their investments as the risk of investing in startups increases.

Unlike the collapse of FTX in 2022, SVB is an FDIC-insured institution, which is why the federal government stepped in. Still, the Fed’s backstopping of SVB doesn’t extend to investors in the banks themselves, only to the bank’s depositors. So, some investors lost significant sums of money in the collapse, which could also have a dampening effect.

Two other large banks failed recently as well: Silvergate and Signature Bank. Regional banks are considered to be particularly vulnerable to higher interest rates, and some experts fear that more bank implosions could be in store, especially if interest rates continue to climb.

If the Fed chooses to pause rate hikes or even reverse course and cut interest rates, then it is possible that today’s inflation of 6% won’t revert back to 2%. In this case, the banking industry, startups, and venture capital ecosystem could all be jeopardized.

A famous Warren Buffett quip is often cited in economic trouble: “Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful.” While the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank brought chaos in the short term, it also presents a unique opportunity for savvy investors.

The fear, disruption, and instability have caused some venture capitalists to retreat, leaving money on the table. Smart investors can take advantage of this window of opportunity, especially as uncertainty about Fed rate hikes persists. VCs who can capitalize on market dislocations by deploying capital more strategically can find value and catalyze more stability in the market.

One resource potential investors can utilize is Gridline, a digital wealth platform that provides access to professionally managed alternative investment funds at lower capital minimums and with greater liquidity than ever before. Instead of relying on traditional financial institutions and their limited options, modern investors can use Gridline to more efficiently gain diversified exposure to non-public assets at lower costs now.

Venture funds typically aim to return capital to investors within 10 years, although disbursements can begin as early as year five or six. In the first 2-3 years, the fund manager generally focuses on investing and growing the portfolio. An exit can be an IPO, an acquisition, a liquidation event, or a SPAC merger.

Let’s unpack time horizons a bit more.

Funds make money when a portfolio company exits. The 10-year time horizon gives venture funds enough time to invest in and grow a portfolio company until it’s ready to exit. For example, the typical company takes 6 years from initial venture funding to IPO. A SPAC is a cheaper, faster alternative to a direct IPO, but not all companies are suited for this type of exit.

An analysis sponsored by the Duke Financial Economics Center finds that M&As are faster than IPOs, taking 5 years on average from initial venture funding to exit.

Since these are median timelines, some companies will take longer, and some will exit faster. But the 10-year time horizon gives venture funds a good chance of seeing investment returns.

A retail investor might find 10 years to be a long time to wait for returns, but it’s relatively short-term for institutional investors like pension funds and endowments. These investors are looking for stability and capital preservation. As a result, they often invest in longer-term funds, with time horizons of 15 to 20 years.

In fact, an INSEAD report has found a surge of general partners (GPs) raising these longer-dated funds. Large PE firms like The Carlyle Group and Blackstone are launching buyout funds with extended holding periods.

These funds benefit from longer “lock up” periods, in which investors agree not to redeem their shares for a certain number of years. This gives the GP more time to deploy capital and generate returns.

While 10 years is a common time horizon for venture funds, some are just 8 years or less. Shorter time horizons can lead to more pressure on GPs to exit early, which may not be in the best interests of the portfolio company. This can result in sub-optimal outcomes, like “fire sales” of portfolio companies.

Similarly, longer time horizons can give GPs more flexibility to invest for the long term and wait for the right exit. This can lead to better outcomes for investors and portfolio companies alike.

Another reason shorter time horizons can be sub-optimal is the J-curve: a typical venture fund’s returns start negative in the early years, as expenses are paid, and initial investments are made. It usually takes several years for the fund to begin generating positive returns. If a fund has a shorter time horizon, investors may not give it enough time to mature and produce optimal results fully.

A Fidelity analysis finds that short-dated bonds, unsurprisingly, tend to underperform their indices more than their all-maturity counterparts. Bond investors should also consider the appropriate time horizon for their investment objectives.

Many venture funds also return capital to investors through “early distributions.” Secondary markets also provide liquidity for investors who want to sell or acquire new stakes in venture-backed companies.

Asset-based lending can enable this type of liquidity by providing loans against the value of stakes in private companies.

Ultimately, time horizons are an important consideration for venture funds and investors. Shorter time horizons can lead to sub-optimal outcomes, while longer time horizons can give GPs more flexibility to invest for the long term.

Much has been said about the venture slowdown in 2022. Though every asset class has cooled, recent data shows that VC activity is beginning to rebound. Another silver lining has been the abundance of opportunities for investors with a long-term horizon.

KPMG’s data shows angel and seed investment increased as a percentage of total deals in late 2022. This is partly due to the influx of new, first-time venture funds.

The dreaded “down-round” has yet to make a non-trivial dent in the venture ecosystem. The percentage of down-rounds has been more than cut in half in recent years to the single-digits. When an anomalous down-round does occur, it often makes headlines and is seen as a sign of trouble in the startup market. But down-rounds are a natural part of the business cycle and don’t necessarily mean a company is in trouble.

For example, a 2019 Forbes article points out that Berkshire Hathaway invested at a significant discount in Paytm at a $10 billion valuation. Today Paytm is worth over $400 billion. Not bad for a company that was “in trouble.” In 2016, Flipkart raised $1 billion in a down-round following a $15 billion valuation. Today, the firm is worth around $70 billion.

Simply put, down rounds are far from a deal-breaker—they’re just a fact of life in the venture world. And in many cases, they present an opportunity for investors to buy into a company at a discount. What’s more, valuations are still strong, despite the slowdown.

As the KPMG report puts it, as of Q3 2022, “valuations have yet to slide meaningfully.” Not only that, but 2022 set a new high for capital commitment. Underlining the value of geographic diversification, some regions are seeing particularly strong growth. In India, for example, fundraising is already more than double the previous record annual high at the end of Q3.

In the face of all this, it’s easy to forget that venture is still a young industry. In Q2 1999, VC funding hit a record $7.7 billion. Last year, it hit $445 billion, with $77 billion in Q4. Even the recent nine-quarter low is an order of magnitude above that peak in the late ’90s. Similarly, the devastating Great Recession saw a massive deficit in funding, but by 2011, funding had returned to 2007 levels.

Returns, too, are robust. Looking at performance for 2008–18 vintages, the median private equity fund returned a net IRR of 19.5% through Sept 30, 2021. Amidst the current public market turmoil, private equity managers “are sleeping well”: A long-term, disciplined approach to investing and the ability to capture attractive, off-market deals is paying off.

Of course, there will be periods of ups and downs—that’s just the nature of investing. But for those with a long-term horizon, the current market conditions present an opportunity to get into the venture game at a discount.

The old-school approach to private market investing is becoming increasingly obsolete. Gridline allows anyone—not just the ultra-wealthy or institutional investors—to get exposure to top-quartile private market alternative investments. And with our low capital minimums, transparent fees, and greater liquidity, we’re making it easier to build a diversified portfolio of private market assets.

Crowdfunding was popularized by platforms like GoFundMe and Kickstarter, which allow individual donors to make small donations towards a cause. Equity crowdfunding takes this concept one step further, allowing anyone to invest in private companies.

Equity crowdfunding is a relatively new way for businesses to raise funds from a large group of investors. The first US-based equity crowdfunding platform was ProFounder, which launched in 2011, but later shut down due to regulatory issues. It wasn’t until the JOBS Act was passed in 2012 that equity crowdfunding became viable.

But what’s the difference between equity crowdfunding and venture capital? While the two concepts are similar in many regards, there are key differences to keep in mind.

A Chicago Booth report highlights that out of a sample of 367 equity crowdfunding offerings, only a single one (0.2%) exited—with a mere 2.5X return. In comparison, an analysis of over 1,000 startups funded by venture capitalists found that 22 percent exited, and 1 percent reached valuations of over $1 billion.

In other words, venture capital has a far higher success rate than equity crowdfunding. The main reason for this is that equity crowdfunding platforms are often the last resort for businesses that can’t get VC funding. That’s a red flag because it means the company likely doesn’t have the financials or potential for success to convince venture capitalists.

The data backs this up, with the same Chicago Booth report highlighting that firms that sought crowdfunding were less profitable and carried more debt than those that got venture capital.

Another difference is that venture capitalists are experienced professionals who make well-informed decisions about which companies to invest in. They do extensive due diligence on a company before investing and have the resources to provide support if needed.

In contrast, equity crowdfunding investors often have limited knowledge or experience in assessing investments, making it more likely that their decisions will not result in success.

An analysis of crowdfunding fraud published by the Association of Certified Financial Crime Specialists (ACFCS) highlights that fraudsters often use crowdfunding platforms to launder money and defraud investors.

Since crowdfunding is open to more people, it’s easier for scammers to slip under the radar and solicit investments without going through the same rigorous due diligence process as venture capitalists.

Venture capitalists use a thorough process to screen investments, making it more difficult for fraudsters to get their money. This does not mean that venture capitalists are immune from investing in fraudulent businesses, but their process makes it much less likely.

Accredited investors have many avenues today to invest in private companies. These investments are reserved for high-net-worth, high-earning, or well-educated individuals who have been deemed to have the financial sophistication or experience to understand the risks associated with investing.

In contrast, retail investors make up the majority of equity crowdfunding investors. They are typically not required to meet any criteria and are allowed to invest regardless of their education, income, or net worth. Equity crowdfunding is a more accessible way for everyday investors to get involved in private investments.

That said, retail investors get paired with businesses that are likely less successful and riskier than those receiving venture capital.

Equity crowdfunding and venture capital have similar goals—to finance businesses in exchange for a share of their profits. However, they differ in terms of their risk profiles, the types of investors involved, and the success rates of their investments.

Venture capital has a higher success rate, is often used by experienced investors, and involves a rigorous due diligence process. Equity crowdfunding is more accessible to retail investors, carries a higher risk of fraud, and has much lower odds of achieving successful exits.