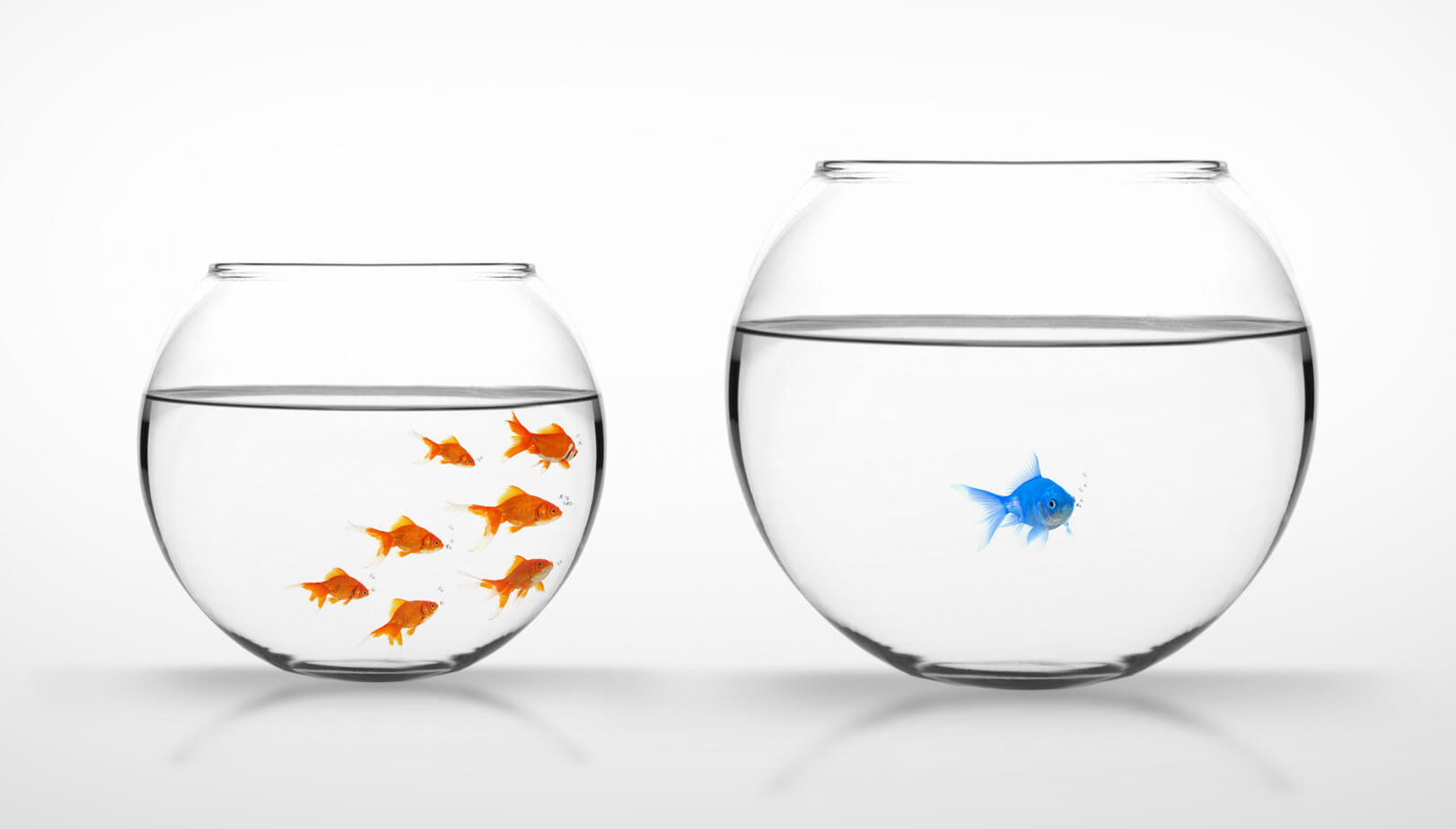

Historically, there’s not one world of investments but two: One for individuals and one for institutions, primarily separated by disparities in access to private alternative assets, resulting in differences in portfolio mix and performance.

This article will explore these differences and how individuals can gain the advantages of typical institutional portfolios.

Institutions have greater access

Institutional investors refer to pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, foundations, and endowments with large amounts of investable capital and long-time horizons. In contrast, while some individual investors have long time horizons, the amount of investable capital rarely competes with the levels managed by institutional investors. For this reason, private investment funds seeking capital typically target institutional investors, resulting in one of the main differences between individual and institutional portfolios: access to top-tier private alternative funds.

As mentioned above, institutional investors manage large pools of capital. They can use economies of scale to source, analyze, conduct due diligence, and select private alternative investments. And due to their large pools of capital and sourcing capabilities, institutions have better access to the most lucrative private investment opportunities.

In commercial real estate, “institutional quality” refers to investment products in core markets that wouldn’t be accessible to individuals, like a high-rise apartment building in Tokyo or an office building in Manhattan.

Institutions also have a significant advantage regarding private equity (PE). Sourcing a PE deal typically takes around one year, three team members, and filtering through 80 or more opportunities. Institutions are capable of high-quality PE origination, while most individuals are not. According to GIIN data, an investing pipeline may look like the below.

Further, institutions have access to better information than the average individual, fueled by their expertise in quickly trading on new market information and better technology for due diligence.

For example, the Bloomberg Terminal provides fundamental quality analysis that’s objectively superior to most of what individuals have access to. Further, institutions take advantage of High-Frequency Trading algorithms that give them an advantage when it comes time to place a trade.

Beyond technological advantages, institutions also have more valuable information networks, which often include direct contact with company management.

Because of these layers of superior access, institutions are seen as “smart money.”

Institutions have a higher allocation to alternatives

As we’ve explored, institutions have better access to investment deals, whether private equity, pre-IPO, real estate, or any deal that benefits from a larger pool of capital and greater access to information. These alternative investments are desirable sources of high returns and portfolio diversification. This naturally results in institutional portfolios having a higher allocation of alternative assets.

Further, many institutions invest in alternatives because they have to. Standardized portfolio management is a requirement of most institutional investors, who are required to hold assets in line with their stated investment objectives. In other words, an institution cannot simply invest in anything that moves—it must invest according to its stated mission and risk tolerance, as its fiduciary duty mandates.

In addition to being forced to maintain standardized portfolios, some institutions use alternatives to gain flexibility within their overall portfolio management framework. Using alternatives alongside more traditional investments, such as stocks and bonds, these investors can gain exposure to more diverse asset classes.

Additionally, alternative assets have higher return potential. By their very nature, alternative assets tend to be less efficiently priced than traditional securities, providing an opportunity to exploit market inefficiencies through active management.

The typical individual investor portfolio is made up of around 70% equities, according to the Asset Allocation Survey by the American Association of Individual Investors. The Vanguard study reports similar figures on “How America Invests.” This is in sharp contrast to institutions. University endowments, for instance, allocate most of their portfolio to alternatives and just a third to equities (with the remainder in fixed income and cash).

The superior portfolio mix of institutions results in performance differences, as well. Research shows that institutional investors “may outperform standard market portfolio benchmarks,” while “the average individual investor underperforms the market,” often to a large degree.

The average individual investor’s performance is further worsening with the rise of retail trading apps like Robinhood. Robinhood has quickly grown to surpass the likes of Schwab and E-Trade by several users, with millions of inexperienced stock investors chasing easy money. At the same time, less than 1% of day traders consistently achieve positive returns.

Institutions have a longer time horizon

In contrast, institutions are long-term investors with a mission that extends into perpetuity. With most endowments and foundations, a mandatory spending rate also requires focusing on finding the best long-term investments to achieve the needed returns. This long time horizon is well suited to exploiting illiquid, less efficient alternative markets such as venture capital, leveraged buyouts, oil and gas, timber, and real estate.

Institutional investment mandates generally center around long-term wealth creation and preservation, which has vast advantages over individual deal investing. As institutions take the long view, they build diverse portfolios of non-correlated assets (non-correlated to the public markets and non-correlated to each other) that continue to work across market cycles.

Individuals are applying institutional investment strategies to their portfolios

The top-performing institutions have come to appreciate that private investments can offer more compelling returns than public market equivalents over long time horizons, and successful investors have maximized their allocations accordingly. These investors also appreciate that building a robust private investment program takes time, skill, and discipline.

Two leading institutional investors, CalPERS and CalSTRS, have benefitted from instituting emerging in-house manager investment programs. Using Gridline, individuals can find potentially talented fund managers and emphasize investing in more diverse strategies and asset classes. In other words, Gridline provides endowment-style investing for everyone.

As we’ve explored, endowment-style investing was previously hidden behind layers of access: Access to more meaningful information, technology, and pools of capital. By providing this access for everyone, we’re making higher-quality investment opportunities available to all.